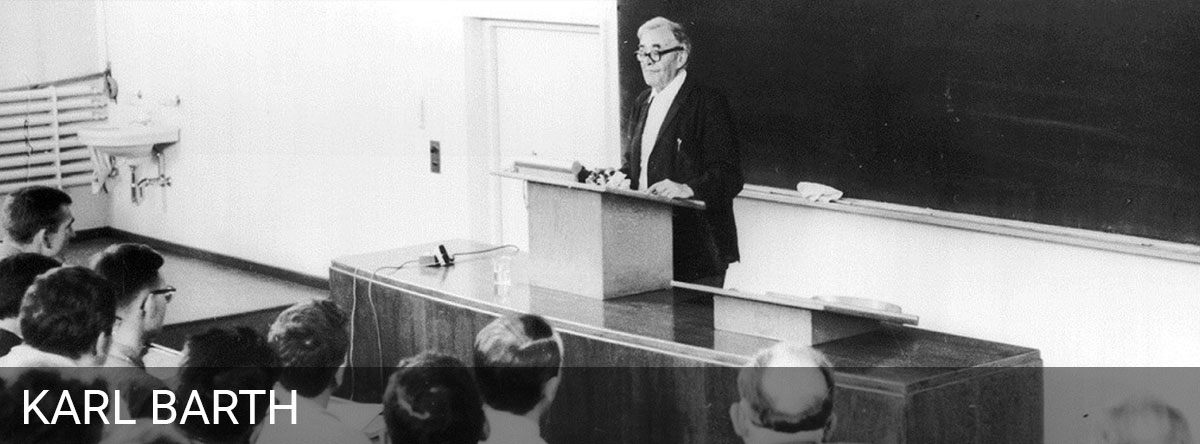

Karl Barth was an influential professor for over forty years. He began his teaching career at the University of Göttingen (1921-1925), went on to hold positions at the University of Münster (1925-1930) and the University of Bonn (1930-1935), before he eventually spent most of his career at the University of Basel with a special chair in theology until his retirement in 1962. Barth had numerous students who traveled from all over the world to study with him during his lifetime, some of whom are still living today. This page serves as an archive of testimonies from Barth’s former students. We hope that students, pastors, and scholars will benefit from discovering what it was like to learn from Barth and the impact he had upon his student’s lives.

Karl Barth was an influential professor for over forty years. He began his teaching career at the University of Göttingen (1921-1925), went on to hold positions at the University of Münster (1925-1930) and the University of Bonn (1930-1935), before he eventually spent most of his career at the University of Basel with a special chair in theology until his retirement in 1962. Barth had numerous students who traveled from all over the world to study with him during his lifetime, some of whom are still living today. This page serves as an archive of testimonies from Barth’s former students. We hope that students, pastors, and scholars will benefit from discovering what it was like to learn from Barth and the impact he had upon his student’s lives.

If you were a student of Karl Barth and would like your story to be included on this page, email us at barth.center@ptsem.edu

Rev. Dr. Cedric Jaggard studied with Karl Barth at the University of Basel through a one-year fellowship in 1938-39. Following his one-year abroad, Cedric returned to the United States just 9 days before Hitler invaded Poland, which marked the beginning of World War II. Cedric studied at various institutions including Dartmouth, Haverford, and Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He eventually went on to receive his ThD from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1950 under the tutelage of Josef Hromadka, John Mackay, and Otto Piper. During his time at Union Theological Seminary, Cedric had the opportunity to study with Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. After completing his education, Cedric served at a number of Presbyterian churches in New Jersey and New York and also taught courses at Carroll College and Lafayette College. He ran social ministries, served as an Army reserve chaplain, and continued mission work even after retirement from the ministry at age 65. Finally, Cedric is the author of Claiming Different Forms of the Good News: Road to a Larger, More Relational, More God-centered Gospel; Overlooked Bible Foundations for Growing in the Faith (forthcoming), which brings together almost eighty years of his theological studies and ministry experience in the church.

Kait Dugan held the following interviews with Cedric Jaggard on December 7th and 21st, 2015. The transcription has been edited where necessary in order to present the material relevant to Karl Barth.

Kait: How did you get to Basel, Switzerland?

Cedric: It was by the grace of God and not by any sort of planning on my part to get to Basel. I was the only American at that time who had the opportunity to go there and do an original theological piece on Barth. It was an act of God. Barth had been teaching in Germany at the time, but known for his criticism of the Nazi style of things.

Kait: Did you take classes with Barth at the University of Basel? What was your first meeting with him like?

Cedric: The faculty take turns guiding students in courses they should take, and it so happened that it was Barth’s responsibility this year. So, I called Barth and requested an appointment. Barth’s English was not outstanding and (his) German was not quite the best at the time. Barth asked me, “Do you have Greek yet?” I replied, “Yes, I majored in it in college.” Barth asked, “Do you have Hebrew?” To which I replied, “No,” and he immediately came back with, “You must start Hebrew right away, right away!” When I rebutted about the course, Barth’s only reply was “You’ll get along.” I was not the top scholar in the class, but it turned out alright. … I never fully thought of myself as a Barthian, but certainly influenced by Barth. He brought me back to the faith of my childhood. At least, that is how I interpreted it at the time. Reading Barth’s Commentary on the Apostle’s Creed, it restarted the faith of my childhood that was more traditional. … Barth, at that time, was really doing the work and then trying it out on his students that he was putting in the Church Dogmatics. He was dealing with the characteristics of God when I was there. So, I remember him speaking on the liebe Gottes (love of God) and

the Barmherzigkeit Gottes (mercy of God) very movingly. He was a spirit of considerable diversity. Sometimes he would seem very extreme in his fierce opposition to Emil Brunner who was over here at Princeton during the year I am talking about. It did seem a disruption of what could have been a quite close partnership. We don’t have to believe everything that everyone else believes in order to feel harmony with them as Christians and to relate to them creatively.

Kait: Was there anything surprising or interesting when you met Barth? Or any other interesting times with him?

Cedric: The most interesting was his open house every other week, which alternated between discussion of theology and the political situation. I admire him so much for his stand in the Barmen Declaration. That was the only formal statement by people in the name of Christ and the church, which took issue with Hitler. Even the Pope didn’t speak out about it, but just about communism. The open houses would be crowded with students from all over the German-speaking world that were there.

Kait: What would it look like to talk about the politics of the day with Professor Barth?

Cedric: Mostly questions from the students who had been there previously. Particularly in Germany, where Lutheranism was so strong, they thought that as long as the state does not infringe upon the church, you must obey the powers that be. What Barth took Romans 13 to mean was that the state, like Hitler’s, was not a legitimate state in God’s sight. It was a good answer to the outright answer of Lutheranism. I can’t remember the details of the theology spoken of. Barth would pose questions to the students about the characteristics of God he was lecturing on at the time.

Kait: You mentioned Barth being influential in renewing your faith. Was there a part of his theology that was so meaningful to you? Or just how he talked about things or were there any specific emphases that he made?

Cedric: When I came in touch with Barth, he kind of brought me back to the faith of my more conservative Presbyterian heritage that I had at home with my church family. It was kind of refreshing to learn about and from him. He just came back to the basics of Scripture with a modern emphasis of his own. He is often called a dialectical theologian going back to Kierkegaard, etc. I see that certain issues where the dialectic was very helpful, especially with Ephesians 2:8-9, in that it pictures faith as a human response to the gospel, as both a provision of God that is for apprehending and appropriating the Christian faith, and the gift of God while it also brings about the responsibility of the individual as a response that is genuine. I found that it (the dialectic) carries through in dealing with theological issues between God and humankind. Certain aspects of God’s truth, humanity, and particularly human response, whether ethical or in some other way, indeed are dialectical. But, I hesitated to apply it to everything under the sun. It was more on these issues I mentioned.

Kait: Can you tell me more about your new book?

Cedric: Through my experience in the church and social ministry, it brought out to me that there are things about the gospel, particularly when we get a little larger concept of a view of the gospel, that should be included, that I felt from the human side of a picture of the human predicament is given by few Christian writers of the past. I drew upon writers from different traditions, such as C.H. Dodd, Gustaf Aulen, and more recently, George Eldon Ladd. I found that there was a broader view of the gospel and a need for the gospel and looking at the human predicament, but more importantly because the heart of the gospel is not our humanity but is the redemptive acts of Christ and finding in those that there were redemptive acts. I found that redemption was not to be identified just in terms of the cross, but that there were these tyrants (Aulen) though he did not have a view of the plurality of the gospel forms, but Aulen did see a plurality of a nice motif in the act of redemption. As I looked at the scriptures, both of the synoptics and the gospel of the kingdom, it did seem that Christ did perform acts that were not just alike but were all extremely costly to him for the redemption of his hearers and those who were in trouble with the problems of the body. The picture of sin, which is so superbly dealt with by Paul, as to the universality of human sin, and yet more realistically entails not just a God/humankind/sin, but the Genesis story where we have additional actors (satanic powers and the world which gets changed), so sometimes we have the ravages of the world to deal with. With personhood attributed to evil powers, when humankind’s life was crippled by sin, that which had been put in human custody, namely the care of the earth, a large part of that also (the ravages of the world, illnesses, demonic possession, etc.) a whole part of human life broadened my view of what the human predicament is. I found that scripture does give us, for each of these, although a different way in each case, the remedy which God provided through Christ’s redemptive acts which were all performed at a very high cost and very hard to compare with one another. Who can think of anything costlier than his death? Maybe his spiritual pain was greater when he cried the cry of dereliction. So, all along the line I try to trace these motifs through regarding the issues of sin which we have in the apostolic gospel and which is in no way lessened as we look at these other things and by his resurrection, which he redeems the new creation of the body of Christ and what is to be the first fruits of our resurrection, he has to come, and that has to be a part of the gospel but not as accomplished yet, but as promised. As we claim by Christian hope and we claim the others by Christian faith.

Kait: Do you have any advice for someone who is a new student in the field of theology as someone who has studied theology for the last 70 plus years?

Cedric: Listen to other traditions besides your own to give the Spirit some space to work in. Starting with other Christians, we do need to be friendly to them and I would hope we could sit down at a large table even though we have different opinions and constantly “proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes again.” Be open and listen to Jesus, because he has much more to say than he told his disciples, and ask the Spirit to give grace to those who differ from you and be open to what they say. We need to be especially appreciative of our Catholic friends and hope that as we do that, we encourage them to do the same. In the parable of the pearl of surpassing value, it does seem to me that where Christ offers us this parable, he is referring to the gospel, and he has what must be a gospel that is adequate in scripture, fuller, and more realistic than we already found it to be. I hope that other traditions might find it and contribute to it, too.