Busch, Eberhard. Meine Zeit mit Karl Barth: Tagebuch 1965–1968 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011), 760 pp. $43.00 (hardback).

Busch, Eberhard. Meine Zeit mit Karl Barth: Tagebuch 1965–1968 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011), 760 pp. $43.00 (hardback).

Reviewed by Matthias Grebe (June 13, 2015)

Dr. Eberhard Busch, Professor Emeritus for Systematic Theology and Director of the Karl Barth Research Centre at the Georg-August-Universität in Göttingen, has authored multiple works on Reformed theology, John Calvin, and the German Kirchenkampf (1933–1945). But he is perhaps most famed for his scholarship on the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968).

In 1975, Busch published his doctoral thesis under the title Karl Barth: His Life and Letters from Autobiographical Texts, which went on to prove an indispensable resource for Barth scholarship. However, it was not until 2011 that he published the Tagebuch, which documents the experiences and conversations Busch shared with Barth during the years he spent as Barth’s academic assistant and personal helper (1965–1968). Although Barth wanted to do so, he never wrote an autobiography, and felt that the main problem with biographies is the lack of honesty. He therefore actively encouraged Busch’s detailing of his thoughts, interactions and conversations, in the hope that some of these might one day be published (5).

The task of reviewing such a text is a difficult one. How does one write a review of a diary containing entries spanning over a three-year period including some significant gaps in time and substantial variations in content and style? Thus to review a diary (or as Friedrich Wilhelm Graf called it, a “theologiehistorische Quelle von eigenem Rang”) calls not only for consideration of Busch’s lively and descriptive narrative of Barth’s life, but also an analysis of the way in which these anecdotes and exchanges converge to form a composite whole that adequately depicts the richness of the subject’s personality, thought, and work.

Goethe-Mozart: 11-24-1965 (26–28)

It is well known that Barth loved the Austrian composer Mozart. In the diary we find a very interesting entry on how, late in life, Barth viewed the arts and considered the difference between Mozart and the German poet and writer Goethe.

After an entry about Barth’s hospitalization, Busch writes about Barth’s renewed interest in the works of Goethe. On reflection, Barth regards himself as more able to talk about Goethe at this point than in 1933 when he wrote the lectures on Protestant Theology in the Nineteenth Century: Its Background and History. But what interests him most are the comparisons that can be made between Goethe and Mozart. For Barth, Mozart was a Hör-Mensch (a person who listens), whereas Goethe was a Seh-Mensch (a person who sees). What Barth means by this is that Mozart understood everything as centred around Vernehmen (hearing), hearing the cosmos—listening to a Klang (sound) with open ears. But what about Mozart?, Barth asks. How did he hear? And how did Goethe see? According to Barth, whereas Mozart was selbstlos (selfless), Goethe was radically selbstbezogen (self-referred), and saw the world in relation to himself; his education was Selbstbildung (self-education). What Goethe therefore missed, Barth believed, was suffering, sickness, death, and all things transitory (Vergängliches)—hence Goethe’s disgust for crucifixes and his lack in interest of Christian art. Mozart, on the other hand, had a life that was filled with suffering. And therefore, even though Mozart was no Church Father or prophet, and even though as a Freemason he actually protested against the Archbishop of Salzburg, he nevertheless felt able to carry a candle through Vienna at the procession of the Feast of Corpus Christi (27).

What is highlighted here is Barth’s particular interest in the way that Goethe bypassed Christianity, uninvolved (unbeteiligt) and without any polemic, in effect treating it as non-existent. Even Nietsche, Barth holds, had to rail against the scandal of the cross, and Hegel actually integrated it into his knowledge of the Geist. In this way, Barth observes, Mozart, though not a model “Christian,” was still constantly forced to confront the Christian faith, whereas Goethe saw it as a thing of the past, something that was “behind” him (28).

Ratzinger-Session, Flight from the living God: 2-25-1967 (229–235)

The diary also has an extensive theological section in which Busch provides insight into how Barth taught and led seminars and colloquia. This is fascinating information for anyone who is interested in Barth’s theological methodology and his role as a teacher of theology. Barth held numerous theological colloquia (see, for example, the account of the colloquium on Calvin, 309–313), but one particularly notable one was on the constitution De divina revelatione of the Second Vatican Council, which was attended by the Roman Catholic professor Joseph Ratzinger from Tübingen, and which highlights Barth’s strong ecumenical and pneumatological interest in his late years.

Busch writes that he and three other students were tasked with devising questions to pose to Ratzinger. Under Barth’s instruction two central questions were formulated (229). The first was on the relationship between the Gospel and Church tradition. The constitution speaks as if the preservation and actualization of the Gospel depend on its transmission by the Church. Should this not rather be the other way around, that the life and witness of the Church—and thus its transmission of the Gospel—are themselves dependant on the Good News of Jesus Christ itself? The second central question asked whether the transmission of the Gospel and the growing knowledge of the apostolic witness are truly safeguarded by the Church and especially the juridical-historical succession of bishops, and whether they are independent of the work of the Holy Spirit.

Barth confessed afterwards that he was impressed by the eloquent and precise ad hoc replies that Ratzinger gave. However, he also remarked upon the very particular structure Ratzinger applied to his answers, and wondered whether there was a hiatus between Ratzinger’s speech and his thought, because he always seemed to offer two options (“either/or” or “on the one hand/yet on the other hand”, 230). In doing so, Ratzinger’s theological thinking was characterised with a catholic wideness and inclusiveness, and Barth noticed (and at the time whispered to Busch) that the alternatives Ratzinger gave were not really alternatives at all, but both views that Ratzinger himself held.

Barth usually remained quiet in these sessions in order to give space for the guest lecturer and allow the students to ask questions. When Ratzinger spoke, however, Barth chose to follow up with one very stern question. Having listened to Ratzinger’s description of the rich tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, why, Barth wondered, was there no explicit mention of the Holy Spirit? And why should this tradition still play such an important part for the Roman Catholic Church? Barth asked Ratzinger whether there was a certain “fear” of the Holy Spirit, a question that appeared to rattle the theologian (though Busch suggests that he was polite enough not to disagree with Barth). Barth ended the session with an appeal that, though both churches agree on certain points, we should not deceive ourselves in thinking that we are at the endpoint or goal. Instead, he said, we are still waiting for the one, apostolic Church (230–231).

On Baptism: 3-7-1967 (242–246)

Arguably one of the most interesting but also controversial topics in CD IV is Barth’s doctrine of baptism, an on-going issue of scholarly debate. Busch recounts a conversation he had with Barth on this matter, which gives us a rare insight into how the CD was written and the way conversations shaped Barth’s dynamic theology.

After Barth submitted the manuscript of his book on baptism to Busch for proof-reading, Busch asked Barth about the difference between Geistestaufe (baptism by the Spirit) and Wassertaufe (baptism by water). Busch questioned whether Barth was drawing too sharp a distinction between the two, to such an extent that baptism by the Spirit can almost be said not to amount to baptism at all. Barth answered with a typically lively “No, No,” on the basis that baptism by the Spirit is the pivotal moment in the event of baptism—it is only under these conditions that the word sacrament can be used, the pure divine act (Handeln) of God through which a human being becomes a child of God (242–243).

However, Barth insisted that this “objective” (243) act of God is not something that can be safeguarded by a minister’s sprinkling water over an infant. Thus the individual becoming a new member of the congregation should be seen as the answer to that which is executed (vollzieht) by God alone through the baptism by the Spirit. Busch interjected by asking whether this meant ripping the two apart, but once again Barth rebutted with his characteristic “No”—that this was not his intention. Instead, he said, his concern to preserve their unity was clearly shown in his emphasis that these two moments are part of one Ereignis (event). In Barth’s view, Spirit and water baptism correspond in the same way that the divine Word and human response do, and they should therefore not be seen as mingling or one swallowing up the other. The personal human response to the promise of the Word of God is not simply a consequence the human might choose or not choose, but is instead the essential moment of the baptism of water itself.

Would this mean, Busch asked, that all infant baptism is invalid? Barth answered that he did not mean that. While infant baptism could never be all-sufficient, it nevertheless represented a valid human response. According to the Protestant infant baptism rites, Barth added, the human response is in some sense included in the substitutionary “Yes” given by the godparents, who are called to bear witness to the Christian faith. However, here it is helpful to remember that Barth’s particular focus was on adult baptism, where the candidate had to respond to the grace of God, saying “Yes” for herself (244).

Busch ended the conversation by asking Barth about baptism by fire. Barth replied that he had yet to say anything on the topic, and that it probably meant the biblical language for judgement. He told Busch to write down his own ideas on it at the right place in the manuscript so that Barth could add his own thoughts later.

Rösy Münger, the will of the parents is the will of God: 5-23 / 5-25-1968 (572–581)

The diary also gives very personal insights into Barth’s life and struggles. One reoccurring topic is that of his somewhat thwarted relationship with Rösy Münger, his first love.

In a moment of self-reflection after sharing a bottle of Tokaji with Busch, Barth opens the conversation with a description of their tragic love story. Rosy did not come from a family of theologians, and Barth’s parents did not approve of the Münger family. They belonged to the liberal Christian Church in Bern while the Barth family belonged to the conservative wing. Partly because of his parents’ pressure and partly for his own reasons, Barth broke off the relationship with Rösy, but he was later haunted with doubts over the decision, questioning whether the advice of his parents really aligned with the will of God on the matter. The only answer Barth received was that “Elternwille ist Gottes Wille” (576)the will of the parents is the will of God. Two nights later—without wine or the usual Mozart this time, but with a bottle of Schnapps hidden behind his books—Barth again showed his vulnerability and shared with Busch some stories about his student years in the fraternity Zofingia, and about Barth and Rösy’s first kiss at a ball. To that day, Busch writes, Barth remained unsure about why he allowed his parents’ will to overrule his own desires.

The importance of the Lord’s Supper: 11-22-1966 (131–135)

As a theologian of the Church, Barth was very much interested in liturgy and its various pitfalls. Even though the section in CD IV/4 on the Lord’s Supper was sadly never written, the diary highlights an insight into Barth’s thought on this matter.

Barth points out the key lacuna of the Reformed Ein-Mann-Betrieb (one-man-operation, 132), and how it can only be filled with the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Something is missing, he believed, if a church service only includes a sermon and no Eucharist! It is this celebration that highlights that something actually happens (geschieht) in the church service—namely, after God’s Einbruch (in-breaking) to our world there needs to follow a corresponding human communal Aufbrechen (out-breaking). For Barth, this obviously had to be the Lord’s Supper as understood in a Protestant sense, not the Roman mass. Busch points out that this view (i.e., that a service is incomplete without this meal) did not represent a new thought for Barth; for many years he had held that Protestant teaching on the topic was lacking.

Leuenberg with church leaders: 2-28-1968 (533–534)

Barth was very much a theologian of and in conversation with the people. We see this engagement throughout his life, which did not stop even in old age. After a period spent in the Swiss hospital, Barth asked Busch to join him at a meeting of Reformed, Catholic, and Christ-Catholic church leaders in Switzerland (524).

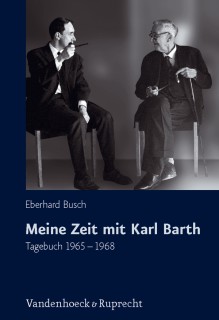

It was a day of reflection, and Barth and von Balthasar were asked to give talks. On arrival Barth showed signs of weakness, and Busch arranged a chair in the lobby (as pictured on the front cover of the volume). Here he was greeted by various church dignitaries as he sat and smoked his beloved pipe. Without a proper manuscript, Barth gave a lively talk on a theme that was close to his heart in his last years: the renewal of the Church. His thesis was that the Church can overcome internal discord if different denominations choose to live in reformational renewal, not in order to adjust to modern society but as a constant act of return to the God witnessed in the Holy Scriptures. It is God, said Barth, who renews through his Word and his Spirit, and in response the Church should live in renewal in order to serve God and our fellow human beings. Busch tells how on the journey home Barth said that, having given his talk, he felt like a “deer being brought to fresh waters” (534).

The Visit to Rome and Pope Paul VI.: 9-20-1966 (82) and 10-5-1966 (83–94)

Barth’s interest in his later years in the Second Vatican Council and the renewal of the Roman Catholic Church cannot be overestimated, as seen in Busch’s entry two days before Barth’s visit to Rome in 1966. Before his departure Barth prepared a number of questions and organised for copies of his works as gifts for Pope Paul VI, which he signed in Latin. He received a warm reception in Rome, and Busch describes with some mirth how much Barth enjoyed the various privileges laid on by the Vatican, including a chauffeur-driven Mercedes. Barth said he was treated like a cardinal (84).

In Rome he had the chance to ask his prepared questions in seminar-style sessions, which sometimes lasted over three and a half hours with six to twelve people present. Barth also met with with Jesuits including Karl Rahner and Professor Dhanis (the director of the Gregoriana), cardinals such as Alfredo Ottaviani, and archbishops including Pietro Parente. Barth conversed with the Pope in French, and, although he remarked that his private audience with Paul VI was the highlight of the trip, the Pope nevertheless did not strike him as strongly theologically versed! The Pope had clearly heard about all the seminar-style conversations Barth had with the Vatican theologians and chose to lead their discussion in such a way that Barth was barely able to make any sustained comment. One mishap detailed is the meeting with Cardinal Augustin Bea. Barth had read Bea’s decree on religious freedom the night before in his hotel room and considered it a fairly lousy piece. He evidently communicated this in their discussion the next day, and the two were unable to find much common theological ground when discussing the topic of freedom (87–88).

Concluding Remarks

As with all of Busch’s works on Barth, Meine Zeit mit Karl Barth is not only invaluable for those working on Barth, but achieves that rare combination of detached insight and genuine intimacy with his subject, successfully depicting the Geist of his friend and mentor. Moreover, his memoirs of those final years with Barth are full of humorous anecdotes (such as Barth’s allowing Busch to use his cigars, tobacco and gramophone but not the wine!, 52–53), personal exchanges and startling—even profane—entries, alongside theological deliberation. The work is comprehensive in its view on Barth’s specific theological, political and artistic concerns, his interactions in the academy and Church, and his friendships and family. It is so extensive that its index lists over 700 separate names (though sadly no theological subject index! Perhaps this could be added in the English translation), and yet it still remains a uniquely composite—and not fragmented—piece.

But does it offer us an encounter with “ein anderer Karl Barth” (5, see also 131–135), markedly different to the one we already know from his works? Such is the breadth of Barth’s whole output that we already have an extremely comprehensive idea of who he is, his theological bugbears and obsessions, proclivities and whims. Nevertheless, the richness of Busch’s description introduces the reader to another side of the multi-faceted theologian: one who, facing death in his old age, witnesses at the end of his life that he truly trusts in the message which he had taught and preached to generations, and that the life, death, and resurrection of Christ continues to transform lives and give comfort and hope. Forthright in his views and unbending in his theological stances, Barth shaped theology in Europe and beyond from the twentieth century to the present day. His vast theological oeuvre can only be complemented by this beautiful depiction of the complexities and vulnerabilities of the man himself and of his relationships with his friends, his colleagues, and his God.

The views expressed here are strictly those of the author; they do not necessarily represent the views of the Center for Barth Studies or Princeton Theological Seminary.